I once heard that when we become aware of our own aging, we tend to reflect on the past. Memories just come back to us in various uninvited ways.

And with a strange feeling, we can sense that time truly flies, like the sand slipping through our fingers, the river water flowing toward somewhere far away, somewhere we do not know.

Sometimes, I am seized by this fear of the unknown, fear of something lying ahead of my life, something beyond my understanding.

At other times, I am struck by a thought, which brings to mind something long buried in the corner of memory, reliving that particular moment in the past. But strangely, I get to see how I reacted in those lived moments.

I saw naivety, foolishness, anger, confusion, regret, passion, and dismay.

I saw the younger me, trapped in my own thinking and exhibiting headstrong, self-righteous behaviors.

I want to understand more about this version of me.

Buddhism says that we are like particles, mingled with the myriad things in the phenomenal world. It reminds us that aging and death are not to be feared because, at every moment, we are being recreated while some parts of us experience destruction.

Body cells die and renew. Thoughts and emotions arise and pass.

We are essentially co-originating with the entanglements in the material world. Our sense of being alive is dependent on something out here.

I am fascinated by the notion of “self.”

The ego and the “cage”

Intuitively, we know there is a difference between the body, or the physical self, and the intangible self, the spirit.

We don’t feel a sense of dissonance when they are aligned well. We are comfortable with our state of being, whatever it is that we are engaged with in life.

Yet, sometimes, an internal discord captures us, reminding us that something is wrong.

But that is not our problem.

We have been educated, trained, and conditioned to think and operate in this world through the lens of subjectivity. But that subjectivity is the product of our cultural contexts.

We assess, evaluate, and measure everything out there from a personal view.

We think that we are the benchmark for judging the myriad things in the world. This is the ego-centric and human-centric ways of understanding our state of existence. In other words, that is the problem of the ego.

A direct consequence of this effect, this cultural and social conditioning, the control of systems, is the separation of us and the world. We have, unfortunately, lost the capability to see the interconnections underlying the appearances of things, between ourselves and the multiple forms of existence in the world.

To some extent, we move about in life to satisfy the workings of the ego. We become trapped by the relative opposites of conceptualizations, the dualistic views on things. When the intuitive understanding of the holistic oneness is lost, distinctions and preferences arise.

Cultural systems, theories, beliefs, and ideologies lend a structured and systematic appearance to the bare ego, legitimizing themselves as the thinking mind makes sense of the world through them.

As a result, while these analytical frameworks and systems help us navigate the complexity of the phenomenal world, they have also assisted in inflating the ego.

When making distinctions becomes a habit for the mind, passions and preferences can be easily energized by artificial sources of influence.

I have realized that my fixations on things are the source of my distress. If I want clarity, then I need to see through the reality that I have been captured by a particular view and driven by my internal desires. And these excessive attachments are the real challenges that I must overcome.

Forgetting into oneness

Chuang Tzu depicts the Perfect Person as having no self.1 It can feel impossible, until we notice the moment it already happens.

Every day, we operate by habits, acquired ways of thinking, and familiar ways of doing things. Yet, intuitively, a flash of thought visits us, makes us wonder, “Why do I think or act this way?”

Like a glitch in a system that is driven by a predetermined script, sustained by auto-suggestion.

Chuang Tzu was suggesting a mystical experience of seeing, observing, and dissolving while moving along with the self, entangled in everyday activities.

When we can see and become aware, we can make the conscious choice of getting unattached.

Yet, this is not to suggest a complete withdrawal from the concrete motion of life. Everything we do, anything necessary for worldly engagement, becomes part of the preparation.

You can step out, not by fleeing the world, but by loosening who you assume you are within it.

I see that it’s possible to restructure my relationship with the world. Forgetting is the doorway.

Forget things, forget Heaven, and be called a forgetter of self.2

Forgetting is not erasing who we are; it is seeing through the identification with the “I” — the self entangled in the outside.

Forgetting allows me to see the artificial distinctions and fixations in my mind, reminding me that I am just one of the myriad things in the realm of being.

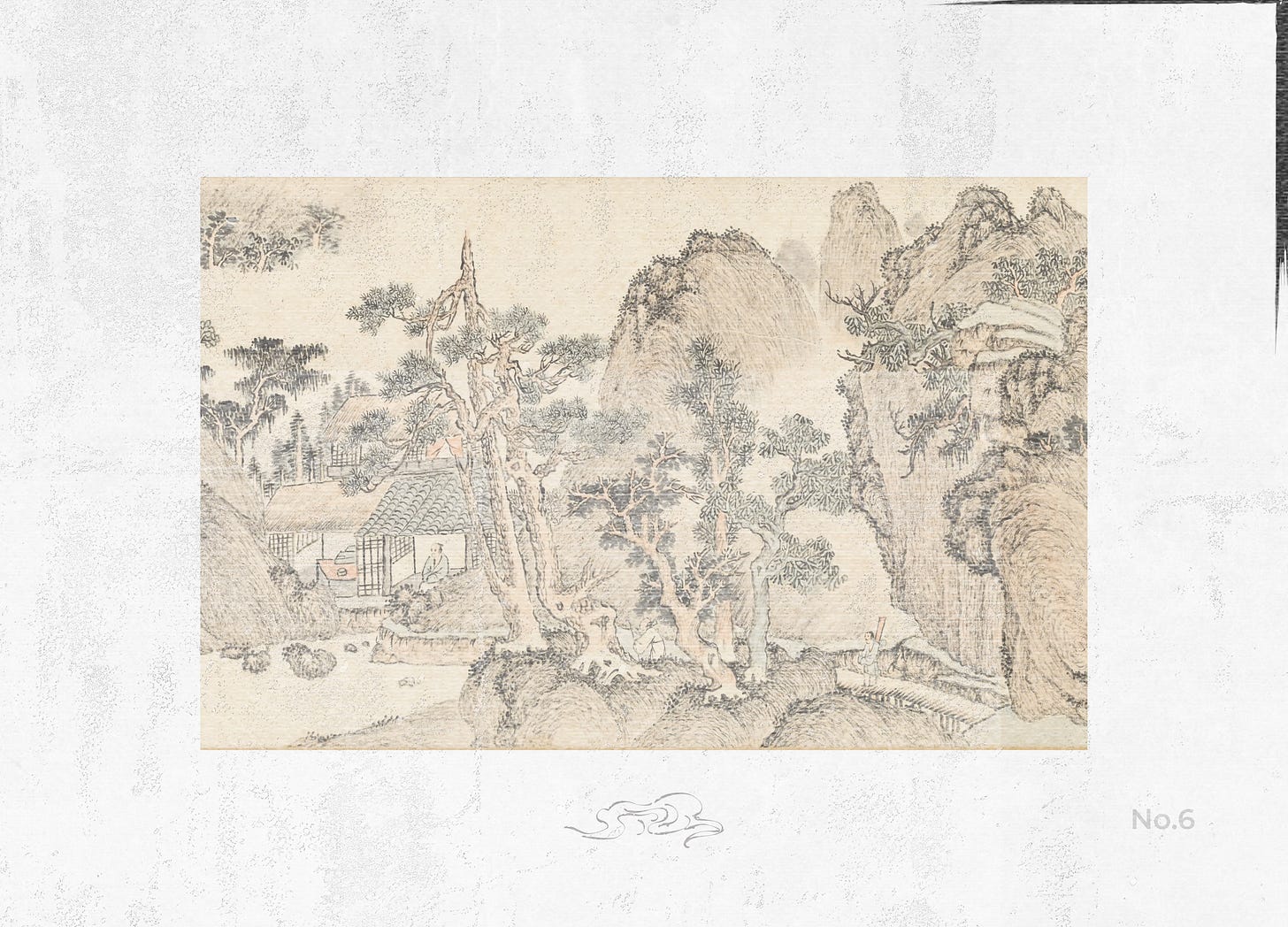

The others, the pine tree, the butterfly, the forest, we are each other’s destiny.

I stop asking questions about “where am I going” because I am not gripped by fear and worry derived from existential distress experienced by the ego. I see them, I understand them, and I am liberated.

I see the similarity between the recluses and me in the notion of self-preservation. I thought that there was a safe and solid foundation of existence waiting for me to discover and build.

You see, I am trapped by my petty, selfish desire and inclinations.

Externally, it’s a way of thinking that “I” can hide myself from the absurd, ironic, and cruel aspects of living, from the existential whole.

Internally, I am stirred by illusions, desires, and expectations in their limitless and unstoppable attack.

Many religious and philosophical teachings speak to this fundamental fear, this anxiety about the state of existence and ultimate destiny.

The person, the receiver of divine message and calling, the enlightened, being inspired to do good things while finding consolation and assurance in “union with God” or some authorities.

I admire their devotion, the purity of heart and spirit. And we need them in this world.

For me, I see my life as part of the eternal transformation of the myriad things in the universe.

The ground of my existence lies in this transformation,3 instead of some hierarchical systems, teleological purposes, or authority of any type. What is required of me is to find my path toward this spontaneous and natural transformation of life.

If I am lucky to find and connect with my gift, my natural endowment, I am grateful for the mysterious arrangement of fate, the infinite Tao, because I know it does not belong to me.4

I am grateful because to be spontaneous is to be free, in alignment with the transformation of the universe. What more do I need?

Every day from now on has become an opportunity to practice my understanding. So I let go of my fixations and ego to follow what is natural in the flow of life.

No more forcing, differentiating, or clinging. No more existential anguish.

Let us forget life. Let us forget the distinction between right and wrong. Let us take our joy in the realm of the infinite and remain there.5

Forgetting is the path for me.

My spiritual liberation lies in unity with oneness, entrusting myself to the forces of change, to the stream of life, where I transmute, evolve, and flow into the unknown.

Fung Yu-lan, “The Happy Excursion,” in Chuang Tzu: A New Selected Translation with an Exposition of the Philosophy of Kuo Hsiang (Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Publishing, 2016), 9.

Burton Watson, “Heaven and Earth,” in The Complete Works of Zhuangzi (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 89.

Heaven is usually interpreted as ziran, or spontaneity, in Chuang Tzu’s thought.

Ibid., “Knowledge Wandered North,” 178-179.

A poetic expression of this thought can be found in Tao Yuanming (365-427 AD), titled “Body, Shadow, Soul.”

“To ride on the billows of Cosmic Flux,

Without joy, without dread;

When it must end, let it end,

There is no need to worry or grieve.”

See Tao Yuan-ming, Gleanings from Tao Yuan-ming, trans. Roland C. Fang (Hong Kong: The Commercial Press, 1980), 172.

The original Chinese of these lines read 縱浪大化中 不喜亦不懼 應盡便須盡 無復獨多慮. 大化 dahua means the great transformation of nature.

This Taoist view of life has shaped the traditional Chinese way of thinking about life, as a popular phrase says, “in the mysterious workings of the universe, there is a predetermined order (mingmingzhizhong ziyoudingshu 冥冥之中 自有定数).

Fung Yu-lan, “On the Equality of Things,” 37.

"Forgetting is not erasing who we are; it is seeing through the identification with the “I” — the self entangled in the outside."

This is the difficult part to understand much less express. The distinctions among the various aspects of self are like a moving mobile in which grasping one part of it moves all the other parts and your action just changed everything.

One especially tricky part is dealing with this concept of the "I." My question, because I am unsure, is whether you are agreeing with those who say that the "I" is a Western concept that is foreign to Eastern philosophies like Daoism, or that the "I" is something else. If the latter, despite having been engaged with Daoist thought for a very long time, I am still confused by its varying descriptions of the "I" and the eternal self.

In Xuanzang's "Cheng Wei-Shi Lun," (Demonstrations of Consciousness Only) the two main illusions are the self and the objects after which the self grasps. 🌲☸️🌲