The Wisdom of Letting Be

3 Chuang Tzu parables on spontaneous flow.

Have you ever found yourself so engaged in a task that time seemed to slip away? It’s as if you become one with the activity, your mind fully immersed and free of distractions.

On the flip side, we've all experienced moments when we are overly self-conscious. Our thoughts wander, and we become disjointed in our actions. This tension between natural flow and self-consciousness is something ancient Taoist philosophers like Chuang Tzu explored deeply.

A key Taoist idea, wu-wei, teaches us how to return to a state of effortless flow by transcending the clutter in our minds and being at ease in life.

It is not about being totally absent from actions but about letting go of compulsive, distracting thoughts and allowing ourselves to act naturally.

When we quiet our inner disturbances, we begin to live in the present moment, aligned with the Tao to flow naturally with our surroundings.

How can we apply this abstract philosophical idea to everyday life? Or is it possible to do so?

On forcing vs. letting be

Once, a sea bird landed in the suburbs of the Kingdom of Lu, and the Duke, eager to honor it, brought it to his temple.

Wanting to offer the bird the best hospitality, he instructed his servants to treat it like a royal guest — lavish meals, splendid music, and a grand reception.

But the seabird, unfamiliar with human customs, didn’t eat or drink. It was overwhelmed and died in three days.

Chuang Tzu criticized the Duke’s good intentions by saying,

This is the method of keeping birds by one’s own (human) standard, and not by the standard of a bird, by what man imagines the bird likes, and not by what the bird itself likes. To keep a bird by what the bird likes, one should let it loose in a deep forest, let it fly over ponds and islets and float over lakes and rivers. One should feed it with little eels and let it fly or stop where it pleases. How foolish it is to make so much noise with an orchestra when its only fear is human voices?1

This parable reveals a common issue in our lives: forcing our will on others based on our own assumptions. We often impose our desires, wishes, expectations, or beliefs on people around us, assuming we know what’s best, whether it’s in relationships or the workplace.

One of the many reasons we encounter obstacles in our specific environments is our subjectivity. The paradox of having subjective views on things is that we have an ingrained habit of following preconceived notions and judgment, which we have accumulated through learning and experience. Yet, when abused, this ability to form personal opinions can obstruct our spontaneous interactions with our circumstances.

It is easier to be captivated by our egocentric perceptions and ways of doing things than to let things unfold naturally. When driven by our excessive subjectivity and preferences, we tend to force our views on what is right and wrong on others, jeopardizing the natural flow of social dynamics.

Therefore, it all comes down to being aware of and, when necessary, letting go of our fixations on particular ideas and values. When we become conscious of the inherent differences among people and things, we can genuinely flow with the tide instead of swimming against it.

Tolerance involves recognizing and respecting differences. And being aware of these differences constitutes a comprehensive understanding of things, for we, as finite beings, can only catch a glimpse of the whole picture by following the totality of the infinite Tao.

With this understanding, it becomes possible to follow one’s natural course rather than forcing oneself into a mold that only suits preferences and fixations.

The empty boat

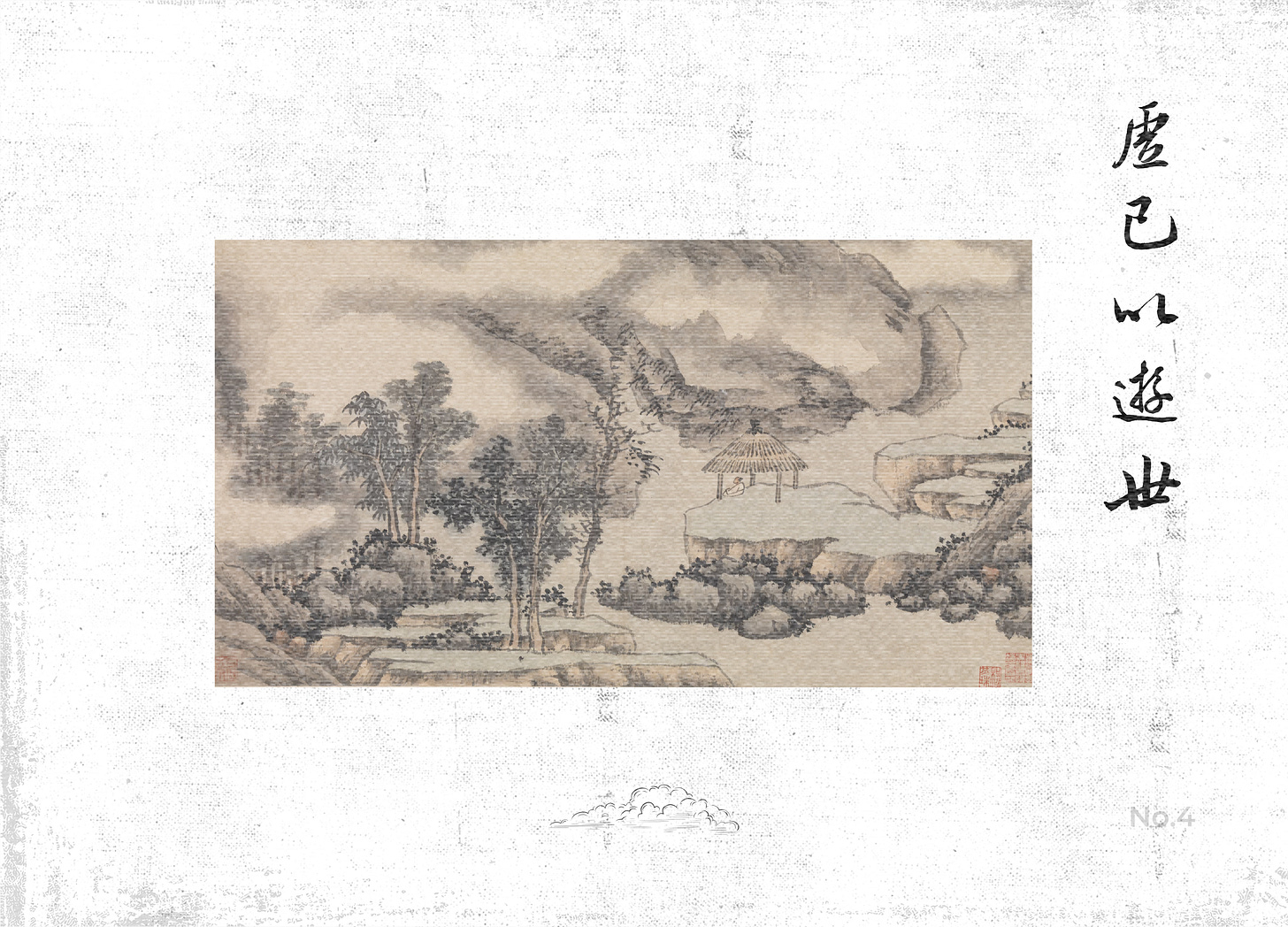

“If a man could succeed in making himself empty and, in that way, wander through the world, then who could do him harm?”

Chuang TzuIn ancient China, a man would regularly commute by boat along a river. One day, as he sailed across the water, an empty boat drifted into his path and bumped into his vessel.2

He was momentarily irritated by the collision and prepared to confront the person steering the other boat. It turned out that it was an empty boat floating aimlessly around in the river. After realizing this, his anger disappeared. How could he be angry with an empty boat?

Sometime later, he encountered another boat on the river. This time, there was a man aboard, and when their ships collided, he immediately shouted a warning. However, the man gave no response.

Irritated, the commuter repeated his shout, but again, there was no reaction. To him, this silence felt like intentional disregard.

His frustration grew, and on the third shout, it escalated into a curse. He became angry at the fisherman because he did not expect the situation to become like this.

This minor incident consumed his thoughts for the rest of the day, ruining his peace of mind.

It's easy to become slaves to our emotions, desires, and impulses. In today’s fast-paced world, we are constantly bombarded by emotional triggers, which makes inner calm a challenge. Yet, if we learn to remain still in the face of these triggers, we can avoid many unnecessary troubles—and that is something within our control.

When we examine the roots of our emotional outbursts, we often find they stem from our egocentric view of ourselves. In short, we take ourselves too seriously. This over-attachment to our ego makes us prone to anger and frustration in conflicts, arguments, and social strife.

The idea of wu-wei — a practice to remain aware of the state of mind in a circumstance — reminds us to let go of these ego-driven distractions, allowing us to flow naturally through life’s concrete moments.

Since we cannot control the actions of others, why let them disturb our peace? In situations of critical importance, such as emergencies and unexpected encounters, we might even ask ourselves: Why did I allow myself to get into this position? Why didn’t I plan for this crisis ahead of time?

Between worth and worthlessness

One day, Chuang Tzu and his disciple were walking along a mountain path, and they came across a massive tree with thick branches and lush leaves. A woodcutter approached the tree, examined it carefully, and then turned away without cutting it down.

Chuang Tzu, curious, asked the woodcutter why he chose not to cut the tree. The woodcutter replied, “This tree is worthless. Its wood is no good for making anything.”

Chuang Tzu smiled and remarked to his disciple that the tree could live out its years in peace precisely because it was considered worthless.

Later that day, they visited a friend who was eager to host them. The friend asked his son to prepare a goose for a feast. The son, unsure which goose to kill, asked whether he should take the one that could cackle or the one that couldn’t. The father replied, “Kill the one that cannot cackle.”

On their way home the next day, the disciple, still pondering the two things, asked Chuang Tzu about the contradiction. The tree was saved because of its uselessness, while the goose was killed for the same reason. Which position, he wondered, was better to take—worth or worthlessness? So, he asked the master what position to choose if he were in such a situation.

Chuang Tzu responded that he would “take a position halfway between worth and worthlessness.”3 Even then, he acknowledged, no position can truly keep one safe from harm. Instead, he emphasized that if a person could remain adaptable and flexible, flowing with the changes of life, they could rise above trouble.

In our own lives, we often find satisfaction in the recognition we receive from others, whether from our achievements or the identities we adopt. These external labels help us navigate the social world and give us a sense of purpose.

In other words, identities and labels can empower us in specific situations while also becoming shackles. The message is that when we become overly fixated on them, we risk becoming entangled in expectations and circumstances beyond our control.

Chuang Tzu’s idea of living “halfway between worth and worthlessness” is a reflection of his deeper awareness that rigidly attaching ourselves to any fixed reality is limiting. Life is full of twists and turns, and embracing the flow of change with a fatalistic acceptance can be liberating.

Of course, living a detached life has its costs and appears impossible. But by living naturally, we can free ourselves from the anxieties of life’s uncertainties. This is the key to becoming unrestrained, moving fluidly through life without being weighed down by the need for approval, control, and overexertion.

Lin Yutang, The Wisdom of Laotse, 229.

Burton Watson, “The Mountain Tree,” in The Complete Works of Zhuangzi (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 158-159. Translation Modified.

Ibid., 157.

Always looking forward to your weekly posts! As I read the empty boat story, I was thinking how we can best apply it to busy, consumed, overwhelmed parents - including those without financial safety net worrying about basic needs.

Compared to work, I struggle often with parenting. I love quiet but my kids are active/ noisy so I am often wrestling with emotional buttons.

Kids, especially little ones, need attention and support almost 24/7 so it’s easy for parents to react emotionally. What would an effortless Wu Wei parenting look like, I wonder. 😊

Really well explained and accessible. I so appreciate your work and sharing the old stories and how they apply today!