Wu-wei is most often referred to as non-action, inaction, “effortless action,” or “unselfconscious action” in contemporary understanding. Another approach focuses on the results it delivers, such as non-intervention, not forcing, or not falsifying. But do these translations capture the essence and scope of it?

From a linguistic angle, a common feature of these interpretations is understanding wu-wei as a negative compound. The term comprises two Chinese characters, wu 無 and wei 為, respectively. Wu means nothingness or non-being, and wei indicates to do or to perform, essentially revealing an active state. Combining these two characters would, therefore, indicate not to act, engage, or perform.

As we know, our actions reflect our thoughts and mental activities. There is an inherent tension if we start resisting and restraining our impulses and emotions. In this sense, we are approaching wu-wei from its spiritual dimension.

In the traditional Chinese language, there was the custom of borrowing characters to refer to something else. In the case of wu 無, its origin is connected to another character, also called wu 舞, which means dance. The picture below shows someone holding something with both hands in a performance. We can only speculate that when early philosophers intended to use the meaning of nonbeing or nothingness, they borrowed the character wu 舞.

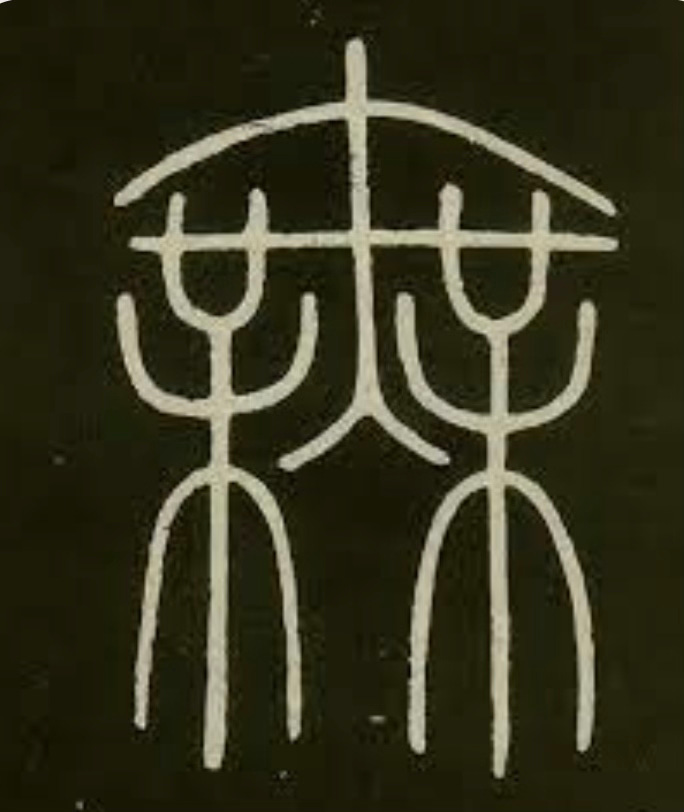

The picture below shows a variation of the character wu 無. It captures the original image of a person holding things with both hands but in a more formalized and structured manner.

Thereafter, the convention has become that wu 無 means nothingness or nonbeing, while the other wu 舞 only refers to dancing. But we already know their connections with the original character (in the pictures above), incorporating more than one layer of meaning. I cannot help but wonder the state in which one gets lost in a trance when we transition from the realm of being, aware of our involvement in activities and motions, to the realm of non-being.

An example of dancing may help illustrate this. Skilled dancers can immerse themselves in movements without consciously controlling and monitoring their bodies. After years of practice and training, they have mastered all the dancing techniques. Thus, with the right cues in a performance, they can get into that unconscious level of dancing without necessarily reminding themselves of every detail and maneuver. In other words, they already do not need to be dictated by instructions, and they can allow themselves to merge with the act of dancing, which is essentially spontaneous.

In this case, the dancer has dissolved the conscious thought of dancing. All that follows is the natural flow of performance. Here, we find the connection between wu-wei and naturalness.

Wu-wei as a principle and practice

We can start with whether wu-wei is an idea that expresses a negative connotation. On the surface, it seems so because it asks us to control our impulses to act and get involved with things. As we can relate, there is a subtle connection between our beliefs and how they affect and shape our behavior patterns. Additionally, our actions and value systems can determine how we interact with others and respond to our surroundings. Therefore, to get wu-wei is to enter into the sphere of consciousness and cultivate a heightened sense of awareness.

In the Taoist system, the sage, or the wise person, appreciates and embodies the idea of wu-wei, as we learn from Lao Tzu’s observation,

The man of superior character is not (conscious of his) character,

Hence he has character.

The man of inferior character (is intent on) not losing character,

Hence he is devoid of character.

The man of superior character never acts,

Nor ever (does so) with an ulterior motive.

The man of inferior character acts

And (does so) with an ulterior motive.1

The critical message regarding wu-wei is about understanding the subtle yet existing line between action and inaction, which is essentially psychological and spiritual. By practicing wu-wei, Taoists act without specific intentions or “ulterior motives.” They would follow what is natural instead of being deliberate and purposeful. To follow what is spontaneous requires one to dissolve obsessions, expectations, opinions, and perceptions. After we have discarded the notion of self, we can enter the state of naturalness.

Let’s illustrate this with an example. Suppose you did a favor to a friend who was in need. According to the principle of wu-wei, you should not harbor any thought of expecting some reward from that friend in the future. And, since you have forgotten about doing the friend a favor, you become unobtrusive in the eyes of the friend, and the social dynamics between the two of you are spontaneous. Wu-wei, in this context, requires you to dissolve the notion of reciprocity and not to have expectations from people.

We all carry some emotional burdens living in the human world. In some sense, the psychological debt resulting from our entanglements with others can be taxing and overwhelming. Chuang Tzu has a beautiful saying describing wu-wei as forgetting, “fish forget one another in rivers and lakes, so men forget one another in the techniques of the Dao.2 Fish wet each other with foam from their mouths when stranded on land. After they swim back to the sea, they will go on their ways and forget about each other. The Taoists practice wu-wei to detach from subjective opinions and preferences without expectations of rewards and recognition. This is the path to access the Tao and restore spiritual freedom.

Therefore, the key to spiritual wu-wei lies in dissolving the notions stored in the mind. As Lao Tzu describes the constant spiritual cultivation of the Taoist as follows,

The sage has no mind of his own.

He takes as his own the mind of the people.3

By refraining from entertaining prejudices and preferences, the Taoist experiences, understands, empathizes, and appreciates the myriad ideas, thoughts, values, and beliefs of others. But, because of spiritual wu-wei, the Taoist does not get attached to prevailing beliefs and tenets as they are essentially external. Alternatively, it can be understood that these ideas have never existed in his mind, including the notion of wu-wei itself, because attachment can be intentional and obstruct naturalness.

We can find a few ideas from Chuang Tzu on how to practice spiritual wu-wei. “The sage uses his mind as a mirror” conveys the lesson that we can try to capture the essence of things by calming our mind instead of allowing it to be disturbed and confused. “Fasting of the mind” informs us of the possibility of training our mind or heart not to get overwhelmed by external values and ideas through cleaning our inner room. We can let ideas flow into the mind without being captured and driven by them.

Wu-wei and roaming the world

Is wu-wei useful, as defined from a spiritual dimension, for us to navigate the world? As we all, to some extent, perceive and interact with the larger environment with particular lenses or analytical frameworks, it can be counterintuitive to adopt the principle of wu-wei to live in the world.

This understanding of wu-wei allows us to be wary of the ideas and thoughts we impose upon ourselves or that which is enforced by society. When we internalize those external morals, customs, and particular ways of doing things, we structure our behaviors and lives in accordance with specific prescriptions. We may have gained the currency of mingling with other people in social groups by fitting in, but it can cost us the opportunity to face the ultimate truth that is usually hidden beneath the superficial reality.

Therefore, wu-wei is asking us to release the psychological and emotional burdens derived from living a life directed by unverified principles and worldviews. It leads us to a journey of spiritual cultivation through which we let open the door leading to our inner room. When the heart is not closed, we can truly open ourselves up and connect with the world.

We can all relate that the myriad things all have their original state or peculiar ways of manifesting themselves. The same applies to the human world, as individuals from different backgrounds have their unique characteristics. We can learn to appreciate this reality of difference with an open heart.

Spiritual wu-wei, therefore, is essentially an internal practice of disenchanting with our perceptions and preconceived notions.

Suppose you have a dispute with someone, as we all do, and you both contend to win the argument. But do you really believe that either of you can win? In what sense? Have you got a glimpse of the truth? Perhaps it is about being on the winning side instead of seeking truth that makes us fall into endless disagreements.

Fundamentally, what are we doing when we engage in unnecessary quarrels or disputes in everyday life? Are we not letting ourselves be captured and dictated by specious ideas and narratives?

From a different angle, wu-wei is a value judgment as it requires us to restrain our impulses and arbitrary actions continuously. The practice of wu-wei is counterintuitive,

“In the pursuit of learning one knows more every day; in the pursuit of the way one does less every day. One does less and less until one does nothing at all, and when one does nothing at all there is nothing that is undone.”4

As a spiritual practice, wu-wei also has an external dimension. When we realize the consequences of meddling and disruptive actions, we do not force others to accept our opinions, preferences, and ways of doing things. At the same time, we can get ourselves untethered from conventional and prevailing views as we do not hold them as constant. In this sense, wu-wei saves us from the shackles of particular ideas and belief systems.

The result that wu-wei brings about is an awareness of the natural order in social dynamics. When we mingle with others without holding any subjective opinions, we develop a lucidity to see them the way they are without causing pressure and tension.

The essence of wu-wei, therefore, is to cultivate a constant awareness of dissolving and forgetting. In this process, we practice emptying the mind without holding anything in our inner room. This is really simple to understand. A full cup cannot hold water. Likewise, a stuffed mind cannot see things clearly.

By practicing wu-wei, we forget about the values, opinions, beliefs, or popular ideologies of the artificial world, and eventually, we forget about the experience of learning and knowing Taoism. With an empty mind, we achieve a state of spontaneous freedom. In this way, we can develop mental clarity to see the breathing space in the intricate social world.

When we can constantly remind ourselves to practice cleaning the inner room, nothing in the world can confuse and enchant us. From that moment, we can genuinely salvage ourselves to live in the present. As we go through this temporary life with wu-wei, we can peel off the inconsequential elements of knowledge and experience stacked over time that could become a drag on us. As we untie ourselves from the shackles and attachments from this life’s excessive and unbearable weight, we can roam the world with a carefree mindset. By merging ourselves with the realm of nonbeing through wu-wei, we can dance in the wind as a free spirit.

Yutang, Lin. The Wisdom of Laotse (Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2009), 143.

Richard John Lynn, Zhuangzi A New Translation of the Sayings of Master Zhuang as Interpreted by Guo Xiang (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022), 148.

Tao Te Ching, trans. D. C. Lau. (London: Penguin Classics, 1963), 56.

Ibid., 55.

Somehow found this in the scrolling. So incredible. THANK you for going through the roots of wu-wei. So many people think it's nothingness, effortless action and that never felt right... i have always seen we have destiny and free will intertwined and I see our part of freedom is to dance through the destiny (or lay down or fight). But I always said, It feels like my job is to choose to dance through the winding path. So finding this was just Great.