Beyond Political Illusions

Part Three: The real path to change in a post-totalitarian society.

Previously in this series, we’ve delved into Václav Havel's analysis of the hidden dynamics underpinning the post-totalitarian system. In Part One, we explored how this system subtly shaped identity and enforced conformity through ideological indoctrination and everyday rituals, exemplified by the greengrocer’s slogan in his shop window.

In Part Two, we examined Havel’s simple but powerful solution of “living within the truth,” against the backdrop of a web of lies manufactured by the regime, understanding how acts of individual authenticity can spark real resistance.

In this post, we’ll see what the opposition force looks like in a post-totalitarian society. Understanding the complex interplay of social dynamics is also helpful for today’s China watchers, as the general social and political circumstances differ significantly from those in Czechoslovakia in the 1980s.

Communist China essentially represents a state of being, a society trapped in a subject culture, a bureaucratic-centric culture, where the elements of civic culture, such as political participation and civil liberties, are still absent in the popular minds. This phenomenon can be observed in over 2,000 counties in China’s vast hinterlands, primarily in the middle and western provinces, which constitute the power base of the Chinese Communist Party’s rule.

Before we begin, I need to reiterate on the post-totalitarian system. A post-totalitarian society, broadly speaking, can be understood as a society governed by a post-totalitarian system, with a single political party ruling at the top of the power structure.

The reason for the prefix “post” is that some radical elements of the totalitarian system, such as the open and brutal persecutions within the political system and political movements that involve the general public, have been absent for some time in the new political and social circumstances. Yet the nature of the regime remains the same, regardless of how much work the regime has put into packaging itself as a friend to foreign capital and friendly and curious tourists.

Therefore, it’s a misnomer to designate the Communist system in China as authoritarian. An authoritarian system is one in which there are elections and opposition parties, as is the case in Turkey and Singapore.

China’s totalitarian system, which was built with the assistance of the Soviet Union, has become softened to some extent due to the integration with the global economic system. Yet, to what extent the regime has changed since 1949 is a question open to all kinds of interpretations. From the perspective of regime and system analysis, the current China and North Korea belong to the same group.

“Did you finish the pie?”

“We'll finish it up tonight.”

“Pass it on to Volodia when you're done.”

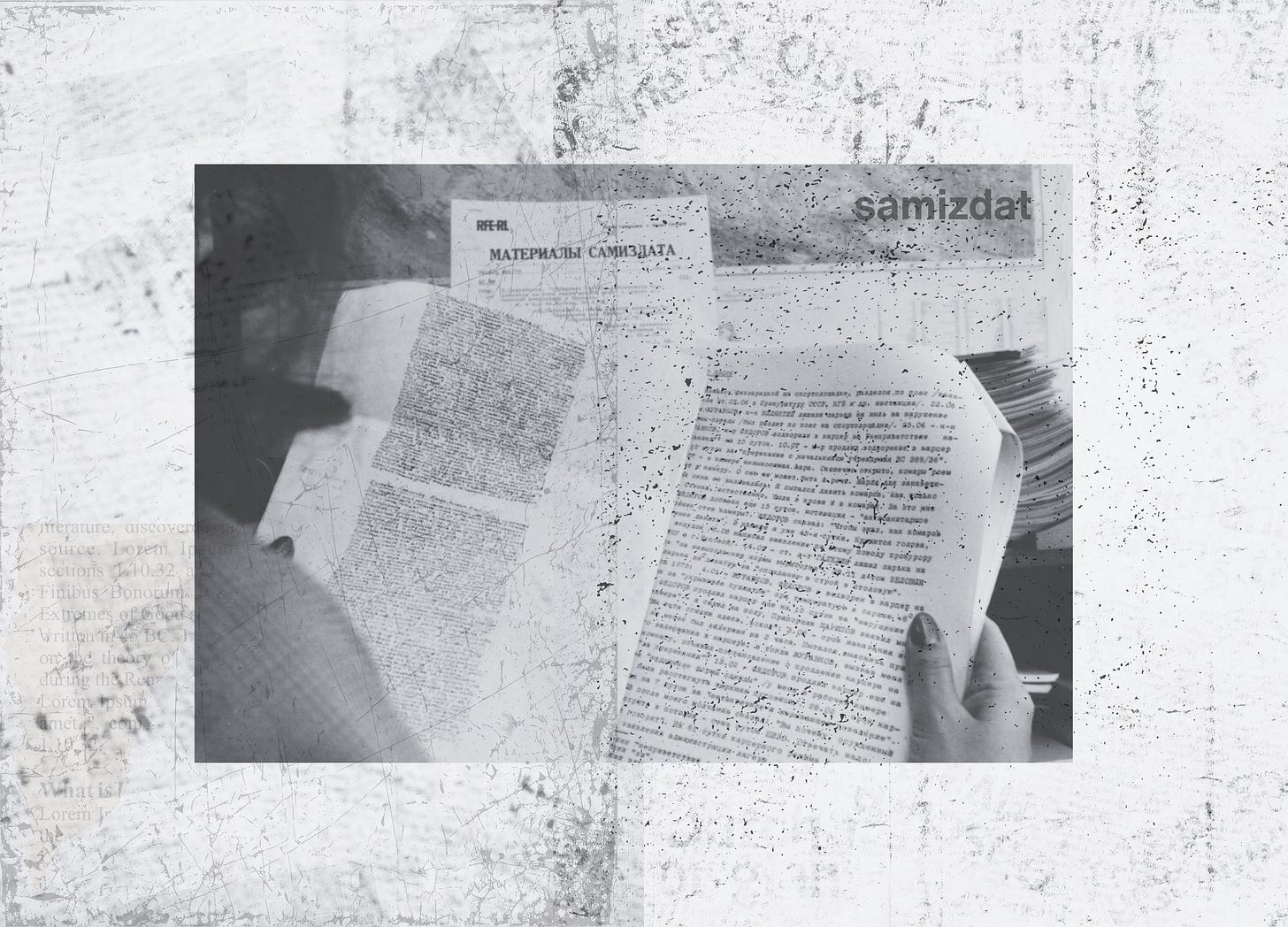

A popular joke in Eastern Europe during the Cold War. Two readers of samizdat literature (forbidden texts among the dissidents) assumed the KGB was listening to their conversation. The true power dynamics

In our previous discussions, we have seen that simply relying on political processes and structural shifts within the post-totalitarian system to yield changes is insufficient. As Havel has explained, real political change first occurs in the “pre-political hinterland” — the sphere where non-political and authentic activities happen. These activities do not necessarily have a political purpose, but they are inherently independent initiatives, derived from common sense and human consciousness.

This indicates that meaningful change arises fundamentally from a shift in the existential, moral, and spiritual order. Without these deeper changes, which touch on the meaning of existence, even the most sophisticated political and economic reforms are superficial and ineffective in bringing about transformations in society.

In other words, the crisis at this level is the real crisis, as one is trapped in a state of being paralyzed without seeing the way out. One is no longer whole on the existential level, but is being tightly monitored and controlled by the state.

If official ideology is the underlying force that dictates the average person’s understanding of existence as part of the post-totalitarian system, then the outward power structure and its networks of control are the necessary mechanisms to facilitate the functioning of the bureaucratic machine and the society under its influence.

In other words, individuals no longer have the choice to craft their existence in such a system that manipulates human consciousness and shared understanding of things. And the system is good at coercing individuals to submit to its sphere of influence. There is no harmony between the individual citizens and the government, as the political order, in essence, is very much predatory and dominant.

People familiar with the red tape culture in communist and socialist states can attest to the reality that their actions can only be approved when they are aligned with the directives and ideological inclinations of the state on the higher level, at the same time catering to the parochial and immediate interests (meaning, bribery and currying favor with officials) of functionaries at the lower ranking government bureaus.

The post-totalitarian system, on the other hand, is utterly obsessed with the need to bind everything in a single order: life in such a state is thoroughly permeated by a dense network of regulations, proclamations, directives, norms, orders, and rules…Individuals are reduced to little more than tiny cogs in an enormous mechanism and their significance is limited to their function in this mechanism.1

Naturally, how we respond to an overall social circumstance/general social conditions can shape the trajectories of our life stories, but our choices also reflect the evolving social dynamics. People can respond to the systemic pressure of conformity with some forms of resistance, but may eventually give up fighting in the face of being institutionalized, often due to feelings of demoralization and powerlessness.

What is dangerously devious about this system that reshapes one’s meaning of existence is that, it has the capabilities and examples to persuade one that the only worthy, respectable, and pragmatic solution to survive and live a “good” life in such a social atmosphere is to learn to fit in and become one of them, just as everyone else is doing.

The moment one starts to believe such a prevailing narrative is the moment one stops exploring the possibilities of their unique modes of existence. The question is, is it still possible to define the confrontation between the standing power structure and the person who is still aware of his or her situation?

Opposition in contexts

In democracies, opposition is institutionalized and openly competes for votes and power, contributing directly to political decision-making and mutual coordination of interests. For the average citizen, participating in the election process is about shaping the outlook of the polity, reshuffling how the political game is being played, and, of course, agreeing to share the burden of policy adjustment.

In traditional dictatorships, opposition is usually considered illegal and forcibly suppressed. It takes many forms, such as a revolutionary and clandestine movement with the goal of overthrowing the regime. It can also be the case that a social group, in proposing an alternative political program, openly challenges the ruling regime as a political force.

In the post-totalitarian system, which does not allow the existence of actual opposition political parties, resistance occupies a unique existential and spiritual space, confronting the regime indirectly by refusing to perpetuate its hollow rituals, lies, and manufactured narratives, thus creating parallel spaces for alternative forms of existence. In Havel’s words,

The opposition is every attempt to live within the truth, from the greengrocer’s refusal to put the slogan in his window to a freely written poem; in other words, everything in which the genuine aims of life go beyond the limits placed on them by the aims of the system.2

Understanding opposition in the post-totalitarian system clarifies why traditional political and legal approaches are likely to fail in producing real change. The complexity of the legal and bureaucratic code in a post-totalitarian society acts as both a tool of control and a mask of normalcy.

As mentioned above, the red tape culture, characterized by bureaucratic complexity, traps individuals, forcing them into passive roles within the machinery of control. As a result, outsiders often find it challenging to discern the true nature of this system, as everything seems to operate normally on the surface, despite often being confused by the opaqueness and elusiveness of how the system is being managed. The legal code, therefore, serves as a deceptive framework that communicates legitimacy outwardly, projecting the illusion of a functioning society while effectively suppressing genuine autonomy and freedom.

Traditional political fights within the power structure, proposing a new, alternative political program, a basket of reforms, will not work because the real battle is at the existential level, not just on a political and systemic level.

This is why the policy of imposing a liberal democratic model and market economy, the so-called “dual transition,” may not necessarily work in such a post-totalitarian society. The spiritual make-up of the nation, its social fabric, mode of thinking, and ways of doing things are not ready to correspond to democratic governance. In other words, without a genuine social transformation, the process of democratization is most likely going to fail.

The “second culture” and “parallel polis”

In the case of Czechoslovakia, opposition there developed alternative forms of resistance — what Havel and his contemporaries termed the “second culture.”3

This second culture manifested vividly in the clandestine production of literature, journals, and artistic expressions known as samizdat, circulated secretly yet widely among trusted circles. Beyond mere dissemination of banned and censored content, this underground culture became a nurturing ground for truthful dialogue, independent thought, and authentic community-building.

Parallel to the official society, an alternative, underground society—a “parallel polis”—gradually emerged in cities across Eastern Europe during the Cold War. Unlike traditional opposition movements explicitly aimed at regime change, the parallel polis sought to live truthfully, building genuine human connections and reclaiming moral integrity within small, everyday interactions.

Havel’s political essays, like the one introduced here, are still banned in Communist China today. We may wonder, how come a piece of writing about the post-totalitarian system in Czechoslovakia is still censored in the largest communist state?

On the surface, as president, Havel was critical of the CCP and its track record on human rights violations. More importantly, his political essays reveal the nature of such a post-totalitarian system. As pointed out by Havel, the foundation of this system is not raw political power, but manufactured lies intermixed with ideological propaganda. A tiny bit of truth would be considered a threat to the regime.

Generally speaking, anyone working in the cultural sphere, including entertainment and education, would attest to the fact that getting a green light from the Publicity Department in China is usually a tricky business. Such was the case when the “Top Gun: Maverick,” a Hollywood movie, struggled to break into the Chinese market upon its release. The reason was because of a scene where it displayed the national flag of the Republic of China (Taiwan) on a jacket.

Why would such a scene bring about controversy? Anyone politically minded in China knows that you can actually display a foreign flag in public, such as in schools. But not the flag of the Republic of China. For decades, the school system has been teaching Chinese students that the Republic of China was gone in 1949. Therefore, an American movie that associates the image of that flag can potentially raise some questions about the country’s most recent history.

Coincidentally, there was a domestically produced movie, “The Eight Hundred,” that depicted the Republic’s resistance against Japanese invasion in Shanghai in 1937. The movie is about the famous Sihang Warehouse fight under the circumstances of the Battle of Shanghai. The roughly 400 soldiers of the National Revolutionary Army’s 524th Regiment were just a glimpse of the battle between the Republic and Imperial Japan, as the war took the lives of over 3 million soldiers and high-ranking officers on China’s side.

The relevant publicity bureau stalled the movie because it displayed the Republic’s fight in a positive spirit, with many scenes showing the national flag of the Republic of China. Why is a regime so sensitive and paranoid toward this kind of cultural activity, after all, it has won the civil war and has all the political and military power?

Havel has told us the answer: any tiny bit of independent initiative can threaten the foundation of this post-totalitarian system that is built on lies and propaganda. In China’s case, any historically minded person would know how the Republic fought in times of foreign invasion and national crisis, and what the CCP did throughout the war.

An Orwellian future?

I think the idea of “second culture” is quite helpful for people still living in political repression, on a macro and systemic level, and a micro, daily life level. And the presence of such alternative spheres of life reveals two possible trajectories:

An increasingly rigid, surveillance state, enforcing stricter and pervasive control over most aspects of daily life, suppressing even subtle forms of dissent.

The quiet but steady emergence of a parallel polis as a significant social phenomenon, fundamentally transforming society from within through authentic individual practices.

In the second scenario, the transformative power of modest, piecemeal efforts is still the key. A better life can only be created by the person who is consciously taking life into his or her own hands.

In the first case, for example, in today’s China, the real work probably has to begin with rebuilding basic common sense and shared understandings of the country’s recent history before talking about social and political transformations.

Václav Havel, Open Letters: Selected Writings 1965–1990, edited by Paul Wilson (New York: Vintage Books, 1992), 186.

164.

193.

Interesting~ In terms of "packaging", your post made me think of clean energy efforts to soften a country's global image, deflecting away from other worrisome discourse. To your point on shifts in the existential, it made me think of Japan. While harmony 和 typically impresses foreigners, locals know that it's these hierarchical social obligations that hindrances progress in many ways.

In a way, "waking up" in the Japan context means shifting away from the traditional, perhaps somewhat opposite from China. And instead of gradual, could it be that these shifts can only be helped by sudden shocks to bring to surface the deeper, simmering undercurrents.