Welcome back to Reading Taoism.

We are reading chapter 15 of Tao Te Ching this week.

This chapter’s theme is the personality of the Taoist sage. I also compare the ideal type of Taoist sage from Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu’s perspectives from which we can learn and apply some practical wisdom to our everyday lives.

Let’s get started.

**15**

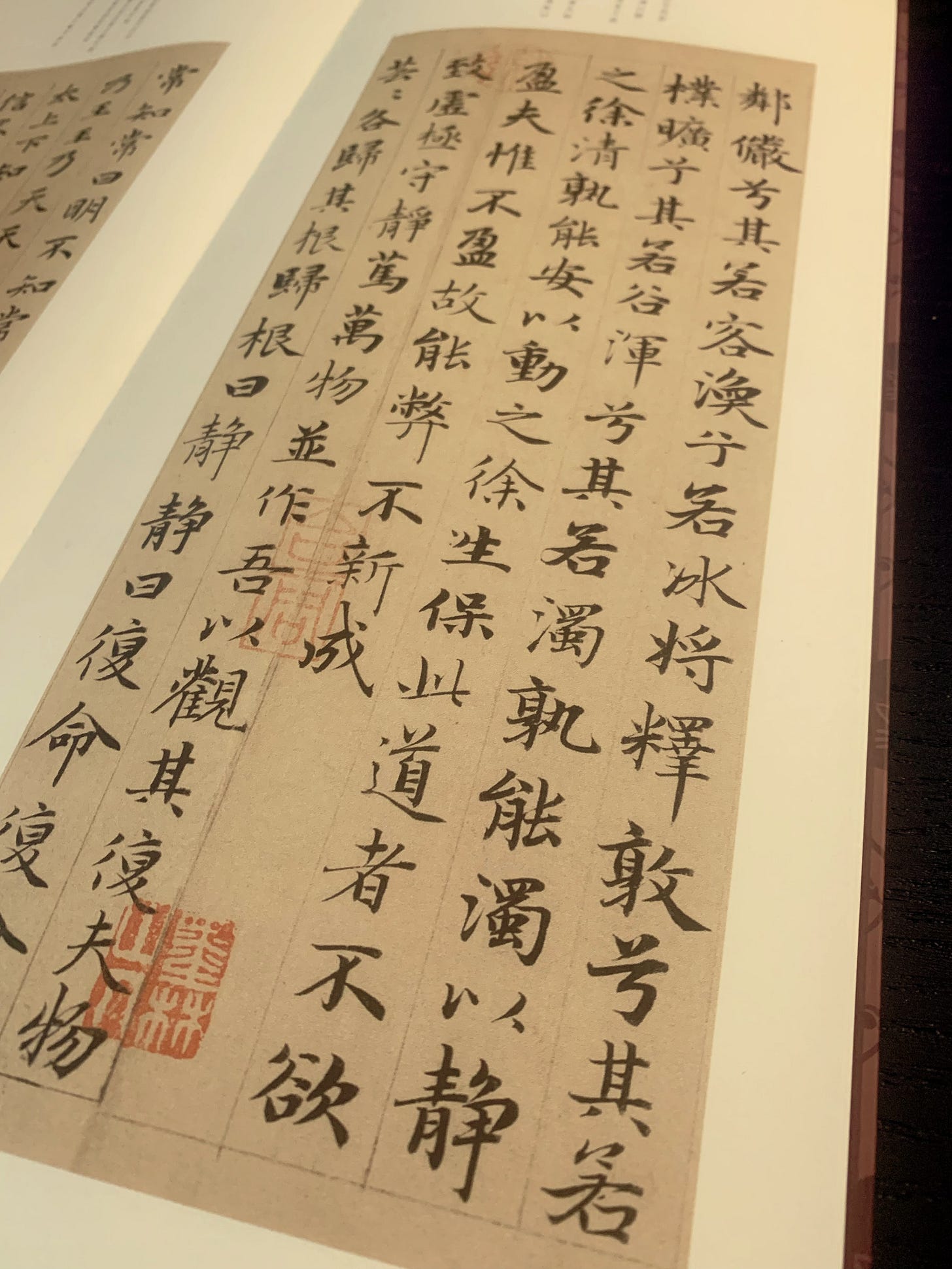

古之善為士者,微妙玄通,深不可識。

夫唯不可識,故強為之容。

豫焉若冬涉川,猶兮若畏四鄰,儼兮其若客,渙兮若冰之將釋,敦兮其若樸,曠兮其若谷,混兮其若濁。

孰能濁以靜之徐清?孰能安以動之徐生?保此道者,不欲盈。

夫唯不盈,故能蔽而新成。

Border-crossing: English translations

#1 Lin Yutang’s version

The wise ones of old had subtle wisdom and depth of understanding,

So profound that they could not be understood.

And because they could not be understood,

Perforce must they be so described:

Cautious, like crossing a wintry stream,

Irresolute, like one fearing danger all around,

Grave, like one acting as guest,

Self-effacing, like ice beginning to melt,

Genuine, like a piece of undressed wood,

Open-minded, like a valley,

And mixing freely, like murky water.

Who can find repose in a muddy world?

By lying still, it becomes clear.

Who can maintain his calm for long?

By activity, it comes back to life.

He who embraces this Tao

Guards against being over-full.

Because he guards against being over-full,

He is beyond wearing out and renewal.

#2 Edmund Ryden’s version

The good Way-farers of olden days were always unseen, mysterious, communing with the abstruse, so deep they could not be fathomed.

{It is because they could not be fathomed, that, }

Therefore, I make this ode for them:

Careful, as he in winter fords a river;

Cautious, as he fears his neighbours;

Formal, as a guest;

Far off, as apart as when ice drifts apart;

Hun like a wooden lump;

Dun like a muddy dump.

{Open like a valley.}

He who can make a muddy pool clear,

It shall then indeed be clear.

He who can make a woman his master,

She shall then indeed give life.

He who keeps this Way does not want to overflow.

{Only because he does not overflow, can he lie hidden and incomplete.}1

#3 D. C. Lau’s version

Of old he who was well versed in the way

Was minutely subtle, mysteriously comprehending,

And too profound to be known.

It is because he could not be known

That he can only be given a makeshift description:

Tentative, as if fording a river in winter,

Hesitant, as if in fear of his neighbors;

Formal like a guest;

Falling apart like thawing ice;

Thick like the uncarved block;

Vacant like a valley;

Murky like muddy water.

Who can be muddy and yet, settling, slowly become limpid?

Who can be at rest and yet, stirring, slowly come to life?

He who holds fast to this way

Desires not to be full.

It is because he is not full

That he can be worn and yet newly made.2

Deeper dive

In chapter 4 and chapter 14, we learned some descriptions and characteristics of the mysterious Tao. And what the Taoists can learn from the rhythm of Tao.

This chapter talks about the character of the Taoist sage.

For Lao Tzu, the ideal type of a Taoist sage is insignificant on the surface. But, a profound and mysterious soul is underlying the everyday outlook.

Such a person is like the “uncarved block” or “undressed wood” without artificial modifications, too much human touch, or even falsifications.

This “uncarved block” symbolizes the unspoiled human nature in Lao Tzu’s thought.

This symbol also embodies a natural representation of things, implying that Taoists should lead a natural life proper to their inborn nature and endowment. Without embracing their own original integrity, the Taoists can not even discover their inner self, let alone form genuine relations with others in life’s journey.

To lead a natural way of life, a Taoist needs to appreciate the value of calm and inner peace. When we go through the ups and downs of this life, we are often swayed and disturbed by those external things. Being entangled with the commotion of life usually leaves us befuddled and unable to see things clearly.

But, being able to reside in calmness helps us regain lucidity and judgment. That’s why Lao Tzu says, “Who can find repose in a muddy world? By lying still, it becomes clear.”

It is also the case that after we find serenity from disturbances in life, we gain valuable lessons and wisdom.

After a period of silent recovery and growth, we come back to life and creation.

Wang Bi’s (226-249 A.D.) comment on this sentence —“Who can be muddy and yet, settling, slowly become limpid? Who can be at rest and yet, stirring, slowly come to life?”— helps us understand the constant cycle of quiescence and activity,

「夫晦以理,物則得明;濁以靜,物則得清;安以動,物則得生。此自然之道也。「孰能」者,言其難也。「徐」者,詳慎也。」

Which can be read as,

“By using reason, we can obtain light. When muddy waters are left alone, clarity can be regained. When calmness is followed by activity, myriad things come back to life. This is the natural way. Asking ‘who can’ implies difficulty. ‘Slowly’ indicates meticulousness and discretion.”

A Taoist is also open-minded, tolerant, and watchful. They know that, like the myriad things in the universe, the human world comprises pluralistic values, beliefs, and norms, permeating and prevailing across time and space.

So, being opinionated and dogmatic without resiliency and fluidity is fundamentally unnatural.

Lao Tzu would suggest embracing the pragmatic principles of humility and not reaching over-full to navigate the world.

Nevertheless, not every person can resonate with the Taoist way. In this sense, it is wise for the Taoists to dim their light and blend in with the chaos of the world.

Spiritual Taoism

The Taoist that embodies the ideal of Tao, from Lao Tzu’s perspective, has a profound mind, expansive and tolerant spirit, mellow temperament, and mysterious soul.

They mingle freely with others in society without trying to look different.

In human relations, they value what is simple, sincere, and natural.

Their ideal life corresponds to the symbol of the “uncarved block,” embodying naturalness and integrity, not shaped by any artificiality.

Compared to Lao Tzu’s sophisticated and wise sage, Chuang Tzu’s “pure individual”3 (真人) can be defined as representing independence of mind, inner freedom, and a transcendent spirit.

In Taoist thought, Tao is the source of values. Individuals can access Tao by themselves through active learning and spiritual cultivation. They do not need intermediaries like parental, religious, or political authority to understand the workings of Tao.

Such an individual is a spiritually awakened and liberated person.

They realize that natural order is possible in the human world only by following the rhythm of Tao, which is accessible to every individual.

The “pure individual” (真人) can navigate the world carefree without being subject to external value systems and beliefs because Tao resides in their heart.

With a transcendent spirit, they can rise above the values and ways of doing things in the human world because they know there is a realm beyond worldly conventions4 (遊方外).

That’s why Chuang Tzu was the epitome of the Taoist ideal,

“He came and went alone with the pure spirit of Heaven and Earth, yet he did not view the ten thousand things with arrogant eyes. He did not scold over “right” and “wrong” but lived with the age and its vulgarity.”5 (「獨與天地精神往來,而不敖倪於萬物,不譴是非,以與世俗處。」)

Thanks for reading!

If you like the content, don’t forget to like and share it with like-minded friends!

Until next week,

Yuxuan

“He is hun dun, an expression which refers to the chaos time before the world came to be in its present form: the cosmic soup.” See Daodejing, trans. Edmund Ryden. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 32-33.

Tao Te Ching, trans. D. C. Lau. (London: Penguin Classics, 1963), 19.

For the idea of the “pure individual”「真人」, Lin Yutang translated it as “pure man.” See Lin Yutang, The Wisdom of Laotse (Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2009), 59.

Richard John Lynn translated it as “authentic man.” See Richard John Lynn, “Da Zongshi [The Great Exemplary Teacher],” in Zhuangzi: A New Translation of the Sayings of Master Zhuang as Interpreted by Guo Xiang (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022), 126.

A. C. Graham, Burton Watson, and Martin Palmer translated it into “True Man.” See A. C. Graham, “The teacher who is the ultimate ancestor,” Chuang Tzu: The Inner Chapters (Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 2001), 84. Burton Watson, “The great and venerable teacher,” in The Complete Works of Zhuangzi (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 42. Martin Palmer, “The Great and Original Teacher,” in The Book of Chuang Tzu (New York: Penguin Books, 1996), 48.

The Taoist transcendence is best characterized as rising above yet not breaking up with this world. For a description of the distinction between “within worldly conventions” and “beyond worldly conventions,” see Richard John Lynn, “Da Zongshi [The Great Exemplary Teacher],” in Zhuangzi: A New Translation of the Sayings of Master Zhuang as Interpreted by Guo Xiang (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022), 145.

Burton Watson, “The world,” in The Complete Works of Zhuangzi (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 296.

Dear Yuxuan,

Thank you for sharing such a comprehensive and insightful exposition on Taoist philosophy and its application in our modern world. Your writing elegantly captures the essence of Taoism as presented by the great sages Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu.

The phrase, "those who know, do not speak," is beautifully exemplified in the lives and teachings of these sages, underscoring the profound nature of silence and subtlety. Your description of the Taoist as one who embraces humility, naturalness, and integrity without the need for show or ostentation, resonates deeply with this very sentiment.

I appreciate how you've drawn a parallel between the "uncarved block" and the intrinsic value of remaining true to one's essence without being shaped by societal or external constructs. The emphasis on individual spiritual awakening and the inherent capability of each person to tune into the rhythm of the Tao without intermediaries is a powerful reminder of our innate potential.

The concept of the "pure individual" (真人) navigating the world without being tethered to external beliefs and values is a refreshing perspective, especially in today's fast-paced and often chaotic environment. The teachings of Chuang Tzu, as you've beautifully quoted, serve as a testament to the freedom and tranquility that can be achieved when one is in harmony with the Tao.

Thank you for your commitment to reimagining and sharing Taoist wisdom for contemporary audiences. The teachings you're putting forth have a timeless relevance and are essential reminders of the need for balance, humility, and naturalness in all that we do.

I'll certainly be sharing this with friends who are on their own spiritual journeys, and I'm looking forward to diving deeper into your content in the future.

namaste, will nemo